I paid a rare visit to what most of us in the North East still call the Hancock Museum in Newcastle recently. Now rather cumbersomely titled Great North Museum: Hancock, this was a regular haunt of mine in childhood, as an enthusiastic member of Watch, the youth arm of the local wildlife trust. Encouraged by my parents, my sister and I would regularly attend talks there (and art classes-more on that later) and, in the years since, I have enjoyed taking my own kids who marvelled at the dinosaurs, the Egyptian mummy and the gift shop tat.

But for me as a boy, the museum was all about the birds; the mounted raptors, the skins of long extinct birds (the museum has two Great Auks, including the only known juvenile in the world) and Percy the Pelican. I was there this time , to clap eyes on a newly renovated piece of master taxidermy by John Hancock himself. John (1808 -1890), along with his brother, Albany were members of the Natural History Society of Northumbria and were instrumental in establishing the first museum at Barras Bridge in Newcastle. Following their deaths, the museum was renamed the Hancock Museum in their honour.

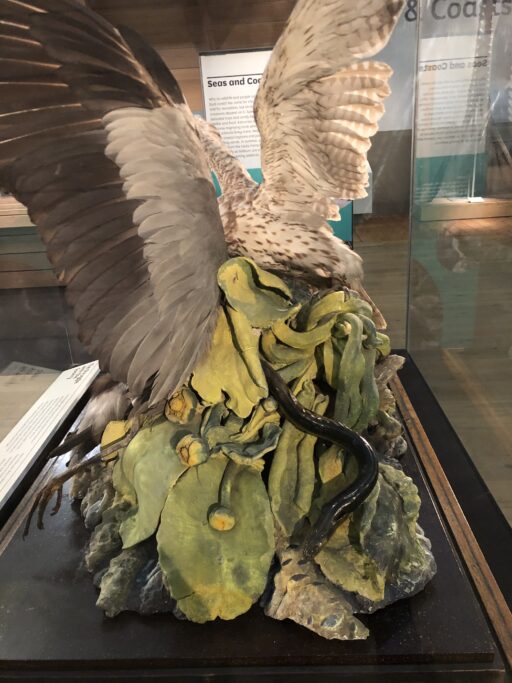

The work I was there to see was originally shown at the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in London in 1851, and is titled ‘The Struggle with the Quarry”.

It is huge, depicting a Gryfalcon and Grey Heron having a proper scrap, and is one of his most celebrated creations. Hancock is often referred to as “the father of modern taxidermy” due to his radical new approach to taxidermy, creating dramatic, realistic stories and scenes with his subjects.

This was not on display at the museum when I used to go there as a kid; if it had, I would have piles of sketchbooks to vouch for it. It would have blown my young mind and I would have pored over it for hours, relishing in the details, like the eel who manages a lucky sidestep to escape the heron’s grasp when all hell breaks loose.

I’m not sure how often Gyrfalcons attack Grey Herons in the wild, but artistic license or not, it is a work of art worth the trip alone.

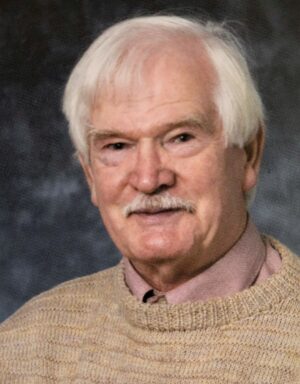

One of the Watch meetings introduced me to another wonderful local naturalist, the local artist James Alder (1920-2007).

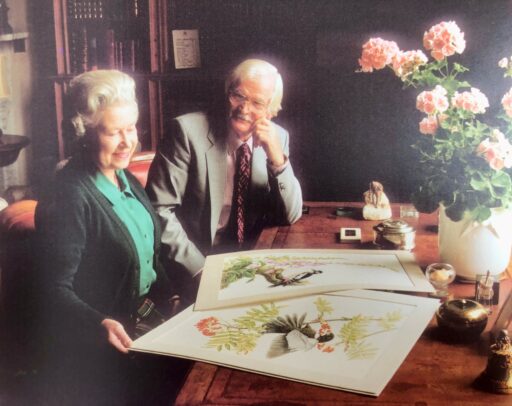

Born in Newcastle, James’ artistic talent as a boy was encouraged by his mother, and by his headmaster, who on seeing a drawing James had done presented the boy with “a leather case containing a complete set of drawing materials that I never even knew existed”. He was given a solo exhibition at thirteen years old and, after winning a scholarship to King’s College, Newcastle, he began an apprenticeship at the age of fifteen, in the art department at Newcastle Evening Chronicle. For twenty years he wrote and illustrated a very popular nature column for the newspaper, bringing his wonderful field observations to a wide audience. Often described as the natural successor to his hero, the celebrated engraver Thomas Bewick, James was a major figure in Natural History in the North East. He worked for several years as the chief animalia sculptor for Royal Worcester and was chosen to to produce limited edition books of “Birds and Flowers of the Castle of Mey” for the Queen Mother and later, the “Birds and Flowers of Balmoral” for the Queen herself.

He received many awards, including an honorary doctorate and masters degree from Newcastle University, and as his final accolade, was was appointed president of the Natural History Society of Northumbira. Many of us unwittingly wore one of his artworks in our youth-the Kestrel logo he designed for the RSPB Young Ornithologist Club in 1965 became a popular badge (or patch) of honour amongst budding ornithologsits for years to come.

James, or Jim as we came to know him, came to our Watch club meeting one day and announced an art competition. We were to draw a bird from the museum collection and he would chose a dozen children from the entrants to be taught every Saturday morning, culminating in an exhibition at the museum. The project was actually extended to 2 years, and Jim was a wonderfully patient, kind and gentle man and I loved going to those classes. What an incredible opportunity we all had with free tutoring from a master like that, and I like to think that Jim wanted to give some local kids a chance, just like his headmaster had done for him back in1933. He even gifted us art materials at times-I vividly remember the pastels that I could never master. Our exhibition ‘Watch in the Hank’ was opened by the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland and we were on telly and everything and it was brilliant.

Many years later, as an adult, I saw James across a crowded room in a completely different setting. I was at the back of a group of people listening to a story he was telling, and I wasn’t sure if he would recognise me. After a moment, his eyes locked on mine and he gave me a wink of recognition, and a warm smile. Chatting later I apologised for never making more of the incredible opportunity he had given me. He was as warm and generous as ever, proclaiming that I was just using my artistic side in a different way.

What a wonderful man he was.

2 Responses

I loved school trips to the Hancock Museum. 😊

If I remember correctly there was a small display in the stone wall (street side) as you went through the front entrance. Is it still there?

Don’t feel too bad about the pastels, I still can’t get the hang of them either. 😄

Thanks Gaina-yes, I seem to recall as small display window too, but not sure if it remains. I didn’t notice it when I was there recently.

The worst thing about the pastels was that Jim used a dodgy pastel Cormorant of mine for the exhibition booklet-it was rubbish! He was always encouraging me to sketch quickly and instinctively, rather than in a deliberate, detailed way and one day I gave it a whirl-he liked it, but I didn’t and I was mortified when that was what was used!