Welcome to part two of The Birds of Tintin, my unnecessary project to name and number every bird drawn by Hergé in his 24 Adventures of Tintin books!

At the midway-point after Part 1 , we are off to South America for the 13th book, The Seven Crystal Balls. On page 2, as Tintin walks from the train station to visit Haddock at Marlinspike Hall, three birds are clearly seen over a ploughed field. These are clearly gulls as, not only are they consistent with Hergé’s previous illustrations of the genus, but they also lack any obvious jizz of other possibilities such as crows, Lapwings or Woodpigeons. I am going to stick my neck out and call these Black-headed Gulls.

On Page 54 as the rain stops, a European Robin (looking a little like its Transatlantic namesake, it has to be said) sings enthusiastically. And on page 56 we see five presumably gull specks over the docks in the distance. This book does contain a stuffed parrot and assorted bird skeletons in Dr Midge’s office at the Darwin Museum, but I haven’t counted those, as it would reduce the credibility of this endeavour. (D0 W9)

There is yet more gull action in Prisoners of the Sun, and thanks to my creation of the new species Hergé’s Gull, we can simply count these and move on, as yet again these are all white, and the addition of yellow bills helps not one bit. No gulls in Western Peru look like this. Hergé’s Gulls one and all. These defaecating irritants appear on pages 3 (thirty eight of them), 4 (ninety nine) and 5 (forty one).

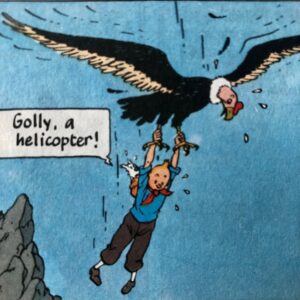

The feathered star of the show here though is the Andean Condor; firstly the bird carries off Snowy to it’s nest before it is promptly shot by Tintin (five panels), then it’s angry mate arrives to attack Tintin before giving him a helicopter ride from it’s legs (seven panels). (D0 W190)

A brief obligatory boat journey aside, the next instalment, Land of Black Gold, is a largely desert-based affair and is completely devoid of birds altogether (D0 W0). Likewise, there are no birds in Destination Moon or Explorers on the Moon at all, which is hardly surprising really. (D0 W0 each)

Hergé , possibly atoning for neglecting birds for years, makes up for it with Tintin’s next adventure, The Calculus Affair. European Robin might not be a new species for the list, but the singing bird on page 10 is much more accurately depicted. Another wild species is depicted on pages 20 and 21 (drawn in seven panels), when Snowy is plucked from a lake by a Mute Swan. And on page 43 Hergé shows three incidental Barn Swallows on wires just for the hell of it, slight plumage aberrations and all! Domestic birds make an appearance too; a market scene in the small town of ‘Nyon’ on page 38 includes five domestic ducks and two chickens. In the same panel there is a white pigeon/dove on a rooftop, and whilst I’d like to call this a wild bird, in all likelihood it isn’t. There is however a small sparrow-like bird on a gutter, and although the rural town setting might make Tree Sparrow a possibility, I am suspect House Sparrow is much more likely. A haystack is disrupted on page 41, and a shocked chicken is ejected from the top. Attempts to consider this a Grey Partridge or tailless pheasant are just wishful thinking on my part. This book, not only a high-point in the series in terms of storytelling, gives us two new species for our list, and absolutely no gulls. Winner! (D9 W12)

Next up is The Red Sea Sharks, another poor entry in terms of bird action, with only a pair of Hergé’s Gulls in the whole book (page 49), despite large sections out at sea (D0 W2). This is, however, two birds more than the next book in the series, Tintin in Tibet, a creative highpoint for the author, but a disappointment for those of us hoping for a Black-necked Crane or a Tibetan Snowcock. (D0 W0)

With The Castafiore Emerald, Hergé appears to atone for the lack of birds in the preceding two books, and puts a bird not only on the inside title page, but also on the first panel of the first page!

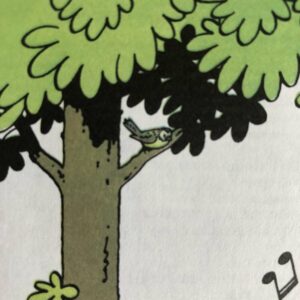

The title page bird, a little brownish job on a tree branch has a streaked back, pale but yellowish belly and a clear malar stripe. The book is set in the month of May, making possibilities here more mouth-watering. The lack of under-carriage streaking makes a pipit unlikely, and although female House Sparrow is possible, the yellow wash to the belly feathers cast doubt on this and suggest Blue Tit. I considered Spotted Flycatcher, but the bill is all wrong. In this habitat, if there were a few upper chest streaks, I would happily have this down as a female Cirl Bunting, but I’m not convinced. Like any self-respecting non-stringer, I’ll err on the side of caution here and plumb for Blue Tit.

The first bird in the story proper is that thieving ring-tailed Eurasian Magpie again! It puts four further appearances on pages 59-62, which for the very astute might be considered somewhat of a spoiler to this thriller of a story. The other bird-related thing of note from the first page, is the fact that Haddock, full of the joys of spring sings from Thomas Nashe’s poem ‘Spring’ “Spring, the sweet spring, Cuckoo, jug-jug, pu-we, to-witta-woo” and tells Tintin to listen to the “chorus of the birds”. These are clearly references to the Cuckoo, Nightingale, Lapwing and Tawny Owl, but only one of these birds makes an actual appearance. A Tawny Owl appears five times from page 40 onwards and is revealed as the “monster” who terrifies poor Signora Castafiore. But it is not only these two wild birds that contribute to the storyline, but there is another of Hergé’s beloved pet macaw’s here too. This bird called Iago, a present from Castafiore to Captain Haddock, would be a Greenwing Macaw if it was not for the blue tail, so it has to be some sort of hybrid. This bird is drawn by Hergé forty-two times, including images of it plucked naked in a dream, singing in a dress and being struck by a magazine in which it features.

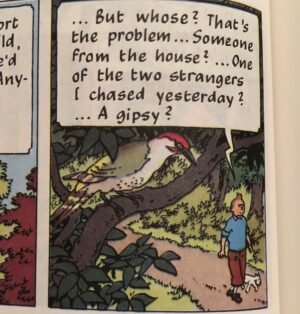

Hergé however, does something very unusual in this book; on page 16 he draws a completely incidental, and text-book accurate, Green Woodpecker! And it won’t be his last… (D42 W12)

Another incidental bird appears in the penultimate completed adventure, Flight 714. When the titular flight is hijacked en route to Sydney from Jakarta, the plane lands on a mysterious Indonesian island, which should be teeming with birds, but a solitary incidental Wreathed Hornbill on page 22 is all we get. (D0 W1)

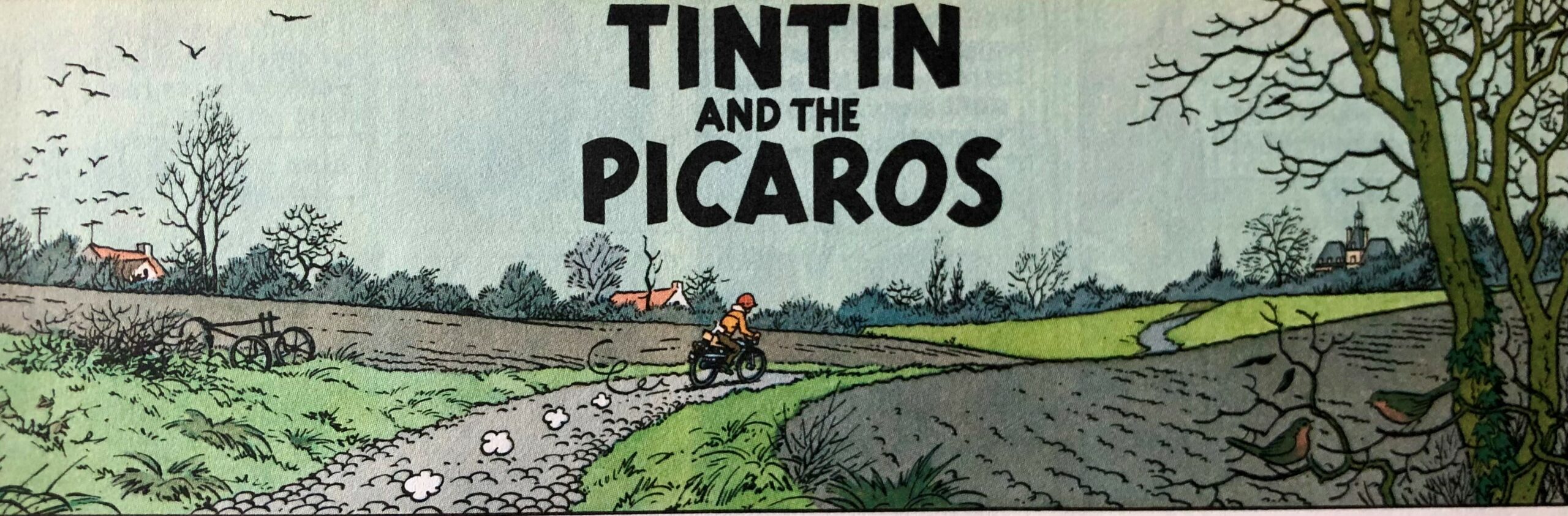

The last complete book is Tintin and the Picaros. Here, Tintin sports a CND badge (yay!) and ditches the plus fours (boo!) and there are few birds to get excited about. The lovely first panel on page one sees Tintin riding between ploughed fields on his motorbike, with two European Robins on a branch to the right and 21 flying ‘M’s in the sky.

They could be (and most probably are) gulls, but having opted for the safest option several times before now, and in light of what is to come later in this book, I am going to stick my neck out here and say that the bird on the right is clearly a Common Buzzard and the others are Rooks seeing it off! Result! Things get even trickier though on page 25 when we see two panels of birds circling a Mayan temple. One looks practically frigatebirdesque, but for the life of me I cannot think of any species I can safely call these. They are birds. Or maybe bats. And there are 41 of them. That’s all I’ve got. I am disappointed too.

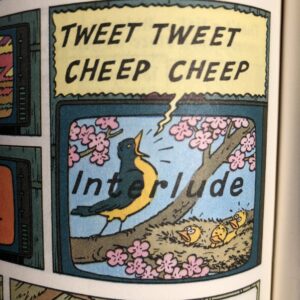

There is a panel with mentioning here though, on page 48.

A television programme is interrupted by a screen message ‘Do Not Adjust Your Set’ which is then followed by an ‘Interlude of a green-backed, yellow-breasted bird at a nest with three chicks, singing “Tweet tweet cheep cheep”. A post on Twitter led to suggestions of Tickell’s Blue Flycatcher, Tropical Parula and Lacrimose Mountain Tanager, which could all be possible, but I think there is a simpler explanation. This is an interlude on television, the chicks are very cartoon-like, and the tweet/cheep call is very basic. I believe that Hergé is here showing us a television cartoon within a comic book, so this is not a real bird. This poses a dilemma; as these birds are neither wild nor domestic, they do not fit my classification. As a result, I have opted to file this alongside other non-living birds from the books, such as the stuffed bird in The Seven Crystal Balls and the Chinese art of The Blue Lotus. (D0 W64)

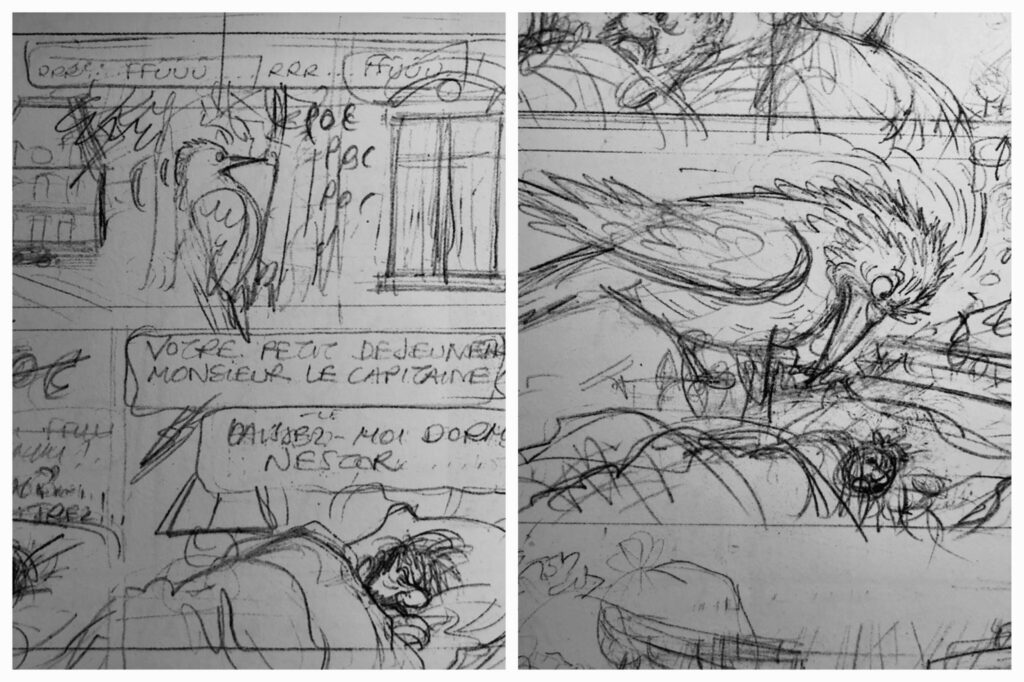

The final book of the series, Tintin and Alph-Art, was left incomplete after the untimely death of Hergé in 1983. It exists in rough sketch form as far as page 42, with the final drawing seeing Tintin being led at gunpoint to his death.

It is fair to assume that he would have escaped, but less certain that the unseen 20 pages would have been littered with new birds to add to my list. The first page does feature another Green Woodpecker though (we know this as Hergé had annotated the sketch), drumming outside Marlinspike Hall as Captain Haddock sleeps. In his dream he imagines this drumming to be a part bird/part Bianca Castafiore drumming on his skull. Excluding this monstrous nightmare ‘bird’ this means that the last bird that Hergé drew for the series before he died was a Green Woodpecker.(D0 W1)

Conclusion

So there we have it! the final scores are in and I can confirm that, over the 24 books, Hergé drew a total of 120 domestic birds (of 7 varieties) and 674 wild birds (which I believe include 24 different species).

Total Bird Count: Domestic=120, Wild=674

The Adventures of Tintin Bird List

1. Wild Birds

- Greater Flamingo

- American Herring Gull

- Vega/East Siberian Herring Gull

- Eurasian Magpie

- Gannet

- (Black-legged) Kittiwake

- Fulmar

- Lesser Black-backed Gull

- European Herring Gull

- Common Starling

- House Sparrow

- Scarlet Macaw

- Blue-and-yellow Macaw

- Black-headed Gull

- European Robin

- Andean Condor

- Mute Swan

- Barn Swallow

- Blue Tit

- Tawny Owl

- Green Woodpecker

- Wreathed Hornbill

- Buzzard

- Rook

2. Domestic Birds

- Goose

- Duck

- Chicken

- Scarlet Macaw

- Jamaican Green-and-yellow Mackaw

- Dove

2 Responses

So pleased you recognised the buzzard being seen off by the rooks. It was worth the journey to arrive at some nicely observed Corvids!

Thank you! It might be stretching the imagination slightly, but the bird on the right is DEFINITELY a Buzzard in my eyes!